Elsewhere I have summarized the doctrine of the Trinity. Below is a synopsis of the story of the Nicene Creed: a short creedal statement that gives an overview of the doctrine of the Trinity.

The story of the Nicene Creed comes complete with a theological villain (Arius) and a hero (Athanasius). This is not just an interesting tale. You will far better appreciate the doctrine of the Trinity if you know a little of how it developed in church history.[1]

First, consider reading the Nicene Creed aloud. It has been ours since the 4th century! It gives the Church of Christ one of the most important doctrinal summaries every written. Notice how Jesus is described. Phrases like “begotten, not made” and “of one Being with the Father” are very important.

The Nicene Creed, ELLC Translation[2]

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is, seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, light from light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father;

through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation

he came down from heaven,

was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary

and became truly human.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in accordance with the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead,

and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father [and the Son],

who with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified,

who has spoken through the prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Most who have been around the Christian faith know that the doctrine of the Trinity is a central part of our faith. Interestingly, the word “trinity” does not appear in the Bible.[3] This does not mean, of course, that the doctrine of the trinity isn’t Biblical as we shall see.

The church father Tertullian (155-220) first coined the word “trinity” in the second century.[4] Tertullian used it to summarize what the Bible teaches about the relationship between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.[5]

Tertullian was quite a story himself.[6] He was from Carthage in North Africa and he came from a non-Christian background. Tertullian was so gifted linguistically that he went to Rome to study law and planned to use his linguistic gifts in a legal profession. But God had other plans. In Rome, Tertullian was converted and when he returned to Carthage his central goal was to passionately study and proclaim the gospel.[7]

This is not to say that Tertullian was the only one who made orthodox contributions to the doctrine of the trinity. Origen and many others contributed to the understanding of the trinity so that much of the doctrine was in place by circa 300.[8] (You can read more about Tertullian in a series of posts by Mike Wittmer).

Yet, a battle loomed. In 318 doctrinal complications arose regarding Christology when a church leader in Africa named Arius arrived on the scene. Arius was a gifted thinker and philosopher. In addition to his intellect, Arius had a great deal of charisma and was gifted musically. He sang little jingles that seemed to answer the questions of newer Christians.[9] Arius’s combination of musical gifts and charisma made him more popular than his doctrine deserved.

Arius argued that the doctrine of the trinity needed a correction. He said that Jesus was not only functionally subordinate to God the Father, but also “essentially” so. Arius insisted that Christ was less in his being than the Father. He further argued that this point was crucial to protecting the unity of God that had rightly been a great emphasis in the Church.[10]

Christianity was young and vulnerable to heresy. When Arius began to question the doctrine of the trinity, people were not used to the whole idea of the mysterious trinity like we are now. The masses wanted a doctrine they could comprehensively understand and Arius gave them answers that seemed to work.

Many were swayed by Arius and began to believe that Jesus was not fully God. Everything was at stake. If Christ is not fully God, then he cannot grant forgiveness of sins in any meaningful way.[11]

By, God’s grace orthodox theologians opposed Arius and a full-scale dispute broke forth in the Church. The relationship of God the Son to God the Father became a huge topic of discussion. Regarding how embroiled people were in the debate, Shelley writes:

One bishop described Constantinople as seething with discussion. He said, “if in this city you ask someone for change, he will discuss with you whether God the Son is begotten or unbegotten. If you ask about the quality of the bread, you will receive the answer that ‘God the Father is greater, God the Son is less. . .”[12]

Eventually, on May 20, 325 A.D., Constantine called a council of the Church to meet in Nicea in what is now modern day Turkey. This calling of the council was in itself amazing. It was the first time such a council was ever convened. It would be a little like the United Nations determining that we need to work through some doctrinal issues and, not surprisingly, it was later to have negative implications.

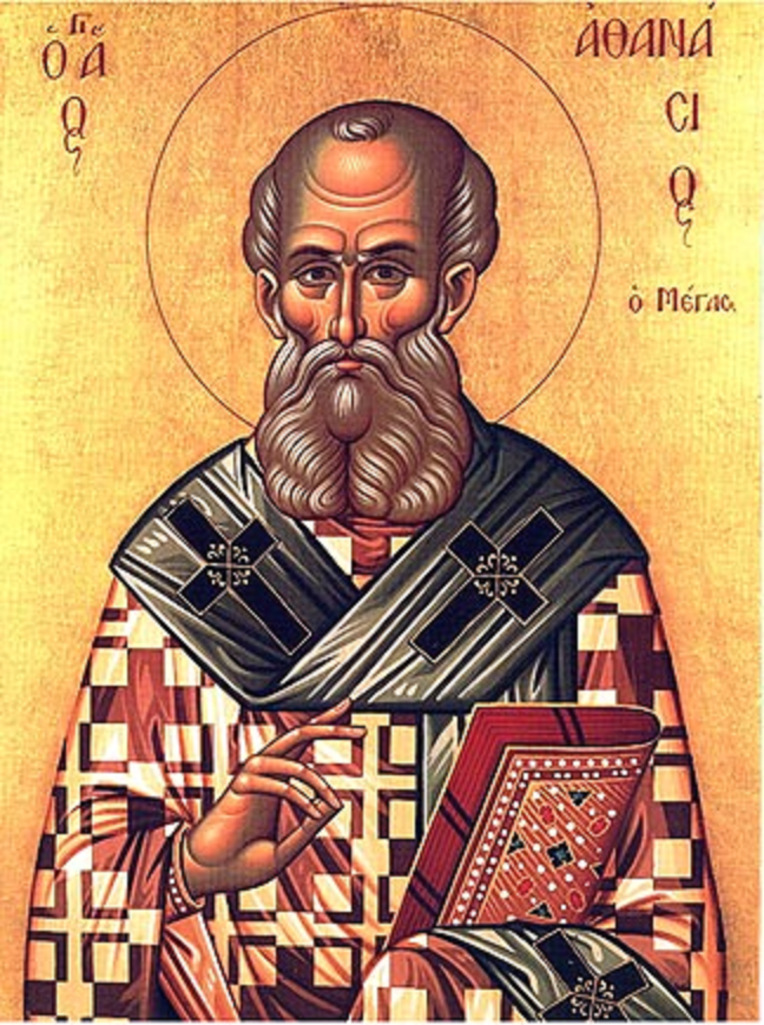

About 230 different leaders met to agree upon a statement regarding the relationship of God the Father and God the Son. One of these came from Alexandria and he brought with him a brilliant and godly young assistant named Athanasius who was to later become the bishop of Alexandria and a great hero of the church.

Arius was his charismatic self at the Council of Nicea. At one point, he burst into a musical version of his heresy:

The uncreated God has made the Son . . .

The Son’s substance is

Removed from the substance of the Father:

The Son is not equal to the Father,

Nor does he share the same substance. . .

The members of the Holy Trinity

Share unequal glories.[13]

Arius’s jingle doesn’t flow that well in English. But it apparently it was catchy at the time. We can be thankful Arius didn’t have an electric guitar! But we are most thankful that once the Church leaders began to study the issues they determined in a relatively short period of time that Arius was teaching heresy. Today, Arianism is known as the heresy that teaches that Jesus is entirely distinct from and subordinate to God the Father.

To clarify the theological understanding of the doctrine of the Trinity, the Nicene council formulated a summary of their position: the Nicene Creed. The Nicene Creed includes this statement about Jesus that today is reflected in nearly all doctrinal statements.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, light from light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father;

through him all things were made.

Regarding the Nicene Creed, Mark Noll wrote:

Not only does it succinctly summarize the facts of biblical revelation, but it also stands as a bulwark against the persistent human tendency to prefer logical deductions concerning what God must be like and how he must act to the lived realities of God’s self-disclosure.[14]

The debate over the relationship of God the Father to God the Son was far from over. It continued over many years and at times it looked as though Arius would prevail. At some points there seemed so little support for Athanasius, the champion of orthodox doctrine, that he entitled one defense, “Athanasius against the World.”[15]

Athanasius was a true theological hero. Five times Athanasius (by this time Bishop of Alexandria) was exiled. But, he stood firm and would not waver.[16] He wrote a famous statement in which he said, my paraphrase, “If Jesus is less than God we have no true hope of salvation.”[17]

C.S. Lewis said of Athanasius. “He stood for the Trinitarian doctrine, ‘whole and undefiled,’ when it looked as if all the civilized world was slipping back from Christianity into the religion of Arius – – into one of those ‘sensible’ synthetic religions.[18]

So you see that the Nicene Creed and the doctrine of the trinity rose out of necessity. Herman Bavinck, in his magisterial book on the doctrine of God wrote, “The development of the truth of the trinity. . . arose from . . . practical and religious need. The church was not interested in a mere philosophical speculation or in metaphysical problem, but it was concerned about the very core and essence of the Christian religion.[19]

An overview of the story of the Nicene Creed should motivate us to endure even when there are conflicts. This is God that we are reading about. What we believe about this relates directly to our salvation and how we believe that we can spend eternity in the presence of the King. It’s worth stretching our minds to consider. This doctrine wasn’t ironed out by stuffy professors who had no clue about life. It was achieved by men of courage and resolve who risked everything to achieve it.

God promised that the gates of hell would not prevail against the church (Matthew 16). Leaders like Athanasius were God’s gift to the Church to protect her from heresy. Five times Athanasius was exiled. Five times it looked to be the end for him. Yet, God used him that we might be here today. Let us sing with the reverence and passion of Athanasius, “God in three persons, blessed Trinity.”

**********

[1] My source for much of this information is chapter 2 of Mark A. Noll , Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity (Wheaton: InterVarsity, 1997), 47–64. It is an excellent introductory book. A much more thorough and technical discussion is found in J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, 2nd ed. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960).

[2] This reflects the expanded version from 381.

[3] R.C. Sproul responds to objections that the word “trinity” does not appear in the Scriptures in his book on the Holy Spirit. R.C. Sproul, The Mystery of the Holy Spirit (Wheaton: Tyndale House Publishers, 1990), 37–46.

[4] Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity, 49.

[5] Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, 113.

[6] R.C. Kroeger and C.C. Kroeger, “Tertullian,” in The Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, ed. Walter A. Elwell (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1990), 1078–1079.

[7] Ibid., 1079.

[8] For a fascinating series of posts on Tertullian’s apologetics, see Mike Wittmer, “Tertullian for Today,” Don’t Stop Believing, April 6, 2015, https://mikewittmer.wordpress.com/2015/04/06/tertullian-for-today/.

[9] Bruce L. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language (Dallas: Word, 1982), 115.

[10] Prior to the third century there was a great emphasis on maintaining the unity of God. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, 109.

[11] Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity, 55.

[12] Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 113.

[13] Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity, 53.

[14] Ibid., 59.

[15] Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 118.

[16] J.F. Johnson and C.C. Kroeger, “Athanasius,” in The Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, ed. Walter A. Elwell (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1990), 95.

[17] Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity, 49.

[18] Athanasius, The Incarnation of the Word of God with Introduction by C.S. Lewis (Macmillan, 1947), 7.

[19] Herman Bavinck, The Doctrine of God (Carlisle, PA: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1991), 333.

What a giant example and encouragement when facing today’s issues.